It’s Time to Visit Slovenia.

Three days in Europe’s hidden gem.

“I think we’re going to miss the cable car…” I muttered to my wife who was seated in the passenger seat next to me. The Slovenian Alps weren’t far in the distance, but the cable car at noon was our last chance before another arrived at two o’clock, and our GPS was giving us an arrival time of 12:03. Having recently arrived at the airport in Ljubljana, Slovenia’s capital, I really wanted to get us to our chalet in Velika Planina so we could enjoy the day. The sky was so clear, it seemed a day we needed to take advantage of.

“I think we’ll be fine,” my wife said, with an unwavering confidence. “The Slovenians seem like they’ll help us if we’re there a couple minutes late.” I wasn’t so sure, but I nodded, agreed, and continued to make our way up to Velika Planina’s famous cable car station.

We pulled up a few minutes after noon, and I told my wife to sprint over to the reception and ask if we missed it. We hadn’t, although it was arriving right then. I grabbed our bags, locked the car, and jogged over to the entrance. There was no snow in Slovenia, but up on those mountains I could see a gleaming white. I had all my gear, my Canon 6D MkII, two lenses, filters, computer, everything really, ready for the trip of a lifetime: a few days in a country I had heard so little of, but one which seemed to contain gems and treasures that were unbecoming of such a lack of reputation in Europe, as well as, broadly, the world.

The cable car took us quickly (perhaps five to ten minutes) from a few hundred meters above sea level to 1,600. Up here, winter still held its ruthless grip over the days and nights. Carrying my camera bag and a larger bag containing all of our clothes, we made our trek up to Koča Ojstrica, a chalet at the very top of the hill. In roughly thirty minutes, up a road that winded around and across the hill’s ski slopes, we finally made it to the restaurant. Taking a quick break, I called my friend Rok, who had been kind enough to organize everything for our two nights here. He helped direct us the final ten minutes or so to Koča Ojstrica and to an experience I’ll never forget. Out through my window, a clear view of the peaks of Kamnik-Savinja Alps in the distance. Fresh bread and cheese on the kitchen counter, a small library down the stairs, and a sauna next to the bathroom. There was still a fire going, so the chalet had a warmth that the fierce wind and cold outside seemed incapable of providing. We settled in, tired from our wake up at 4:30AM in London, and I prepared for the few days ahead.

At about half past 4 o’clock, I began to see the colors change on the peaks. A bright blue was turning to yellow, and slowly to gold. As a photographer, this was the moment I had been waiting for. What followed was a sunset the likes of which I had never seen before. Up on those Slovenian Alps, winter’s soft air seemed to guide the sun’s setting light onto its peaks, the land bathing in the day’s last warmth. I took what felt like a thousand photos, marveling at what I was witnessing. Nevertheless, I am not a mountaineer, and the cold inevitably got to me. I had to head back inside the chalet to warm up. My wife was making pasta and I took this as a good cue to get ready for an early dinner and prepare for some astrophotography at night. Taking my jacket off, I glanced once more through the window and towards the breath-taking view of the Alps. To my surprise, what was orange light had now turned a delicate pink. The clouds which had been set ablaze by the sunset now seemed to float in a heavenly fairytale.

Nightfall at Koča Ojstrica.

A sunset I thought could get no better had suddenly become one it would be impossible to ever recreate, it seemed. Here I found myself, gazing out at a sunset in Velika Planina, high up on the Slovenian Alps, in a shepherd’s hut turned chalet. It was a moment to pinch myself, just to make sure I wasn’t in fact dreaming, still drooling on my pillow back in Bermondsey.

Slovenia, it would turn out, was full of surprises. My experience in the first couple hours at Koča Ojstrica would not be an anomaly, rather a cue for the days ahead. The night sky on the slopes would be so full of stars that it would remind me of French Polynesia, a place so far removed and so different to where we were now, rather than one closer and more similar, like Norway or England. Slovenia seemed to defy expectations.

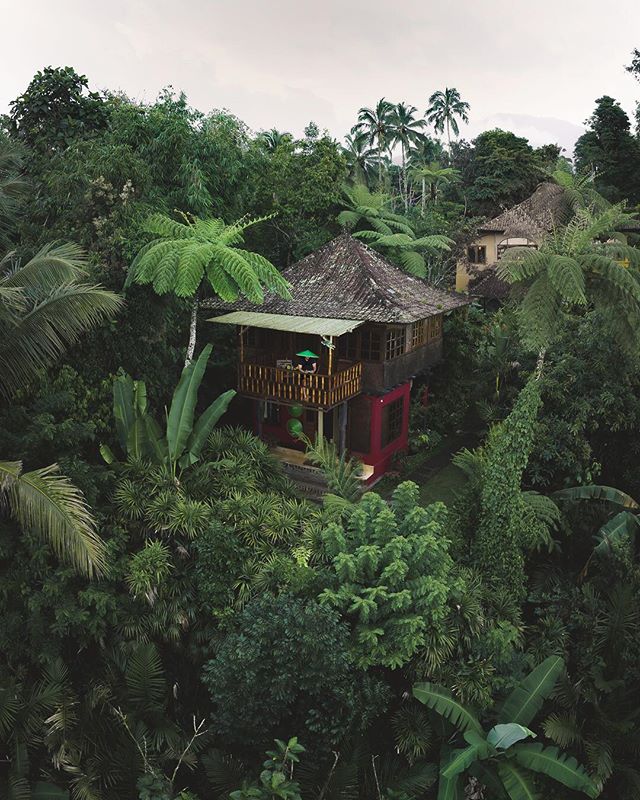

We would find out, for instance, that the wines in Slovenia were remarkable and, yet, unknown to most. Slovenia’s love and abundance of hot springs apparently yielded the perfect waters and warmth for grapes unique to the region. It should be unsurprising then, as a country which shares a border with Italy, if they could grow good grapes, they’d make a damn good wine. To boot, Slovenian food, which I knew nothing about, was powered by an ability to obtain fresh ingredients from all across the country and get it to the center quickly, maintaining its freshness. Fish and seafood came from the Adriatic, only two hours from Ljubljana. Fertile farmland was everywhere, with acres of flat, flat land being dwarfed by the Alps in the distance, in a stunning juxtaposition that seemed to invoke some Slovenian spell under which I was falling. Those same slopes where our chalet was nestled in the snow would—in the summer—become the home of roaming cattle and livestock, transforming the landscape from a pristine Alpine ski resort, to a cultural experience. Farmers stay in shepherd’s huts, have their own location of discussion (dubbed “the Parliament”), sell fresh cheese, and embrace the avid hikers who visit from the cable car station below. The more I learned about Slovenia, the more I understood how brutally wrong I had been and how truly little I actually knew about the country.

Unsurprisingly, Lake Bled was one of those things I did know about the country. A small lake with a church on an island in the middle—how could someone miss that? It was a must for my wife and I, so we left early from Velika Planina to drive the 45 minutes it takes to reach Bled. We met up with some lovely people at the tourist information center and got a couple tickets to the Pletna boat trip, a short, one hour roundtrip journey to the church on Bled Island. What made it special was the traditional “Pletna” boat that was used, powered by one man with two oars, whilst its passengers sat seated under a colorful umbrella. Before heading to the lake, overcome with hunger, we decided to venture into a Mercator (a typical Slovenian grocery store chain) next to the tourist information center in search of any food we could find. And by the meat section in the back, we found the holy grail of freshly fried foods. Ham and cheese crockets, popcorn shrimp, cod, chicken nuggets, potatoes, you name it. It was so cheap and delicious we would have another meal at a Mercator just a day later.

A traditional Pletna boat ride in Lake Bled.

But I digress.

We took a short and frankly, extremely pleasant, drive down one side of the lake. Lake Bled is actually relatively small for a lake, covering only 145 hectacres, so the drive was brief and we quickly found the Pletna boat starting point. With a gentle breeze in the noon air and clear skies, we could not have chosen a better day to hop on a Pletna. In a boat filled with around eight other tourists, it took us 15 minutes to arrive at Bled Island, our Pletna’s wake the only thing disturbing the lake’s still water. At the top, a little cafe with traditional Slovenian cakes and a cappuccino on a table outside overlooking the lake. It was 10 Celsius and I found myself sunbathing for the first time in 2019. Another moment to pinch myself.

Unfortunately, we had to run to lunch to meet the Slovenian Tourism Board, Feel Slovenia, so we cut our time on the island short and took the first Pletna back, hopped in our rental car, and drove the fifteen minutes to Vila Podvin, a restaurant with awards three years running for its refined take on the foods Slovenians have grown up eating for centuries. Our waiter, an extremely kind and generous woman who also knew Rok from Velika Planina helped lend a background to every dish, demonstrating the new-found pride of the Slovenian people in their country, culture, and, in this case, food.

“So this wine is from a region about thirty minutes away from here. The fish you have on your plate was caught in the Adriatic which is only two hours away, so it is really fresh, and the polenta is also made in Slovenia. Everything you have there is Slovenian!” She exclaimed joyfully at one point. I smiled back, excited to eat what looked like a dish from Chef’s Table and marveling at the enthusiasm she had.

Full and with some chocolates for the road in our hands, we left back to Velika Planina. On our way up the slopes, another unbelievable sunset to witness, one last night in the Slovenian Alps at Koča Bistra.

Early in the morning, we had to leave once again. To see much of Slovenia, we understood we’d have to sacrifice sleep. We met Rok at the cable car station, had a good chat after corresponding only over email and phone, and said our farewells. Our next destination was Postojna in the Inner Carniola region at the southwest tip of the country, only 45 km from Croatia and less than 40 from Italy. With the Alps fading into the distance in the rearview, we arrived at Postojnska Cave Park and our hotel, Jama, a four-star hotel located only a few minutes walk from the park’s world-renowned cave system. We checked in quickly, and immediately got ready to head back out to go to Predjama which would hold a sight I will never forget.

Take a car or bus fifteen minutes from Postojna into Predjama, and you’ll find yourself encountering a castle like no other, one straight out of a European fairytale. Perched on a cliff, the medieval castle sits at the mouth of a massive cave, the cave’s entrance visible above the castle’s roof, poking out into the sun. Predjama Castle as it is known, was constructed in the mouth of a cave as a hideout and refuge for generations of different Slovenians who needed safety in desperate times. While the castle is short on amenities and comfort, its back door leads directly into the cave, with an extensive tunnel system (some of which lead to the outside, a literal back door to escape any pursuers) having been carved out and mapped centuries ago. The castle is known most for its “Robin Hood,” Erasmus Predjamski. Erasmus, known for robbing the wealthy and giving to the poor (in some cases, not all), came into conflict with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III in the 15th century. The emperor, furious with Erasmus for killing the commander of the imperial army over an insult to Erasmus’ friend, wanted him captured and executed. He pursued Erasmus through the country, until Erasmus found refuge in the cave castle of Predjama. The emperor, desperate to seek his revenge, laid siege to the castle, blocking access for food and water, attempting to starve Erasmus out of his hiding spot. Unfortunately for Frederick III, he did not have an understanding of the system of cave tunnels shrouded behind the castle structure. Erasmus was using one particular tunnel which led to another part of the cliff fifteen minutes away to not only obtain food and water, but continue his robberies. Once a thief, always a thief in this Slovenian renaissance tale. The castle is a true wonder. Few manmade structures are so striking, so integrated into nature and human history that they reflect not only the tale of a land, but of a culture. This was one of them. I actively tried to freeze the sight in my head, hoping in some way I could cement this experience forever. My camera would capture the rest.

From there, we went back to Hotel Jama where I grabbed my tripod and we headed into the world-famous Postojna Cave. Not knowing what to expect, we followed the guides onto a makeshift, miniature train leading into a dark hole in the wall. With a couple alarm bells, the train sets off, barrelling through that aforementioned dark hole in the wall. Maybe one hundred meters have passed behind you and the lights come on. Just a foot or so above your head, a rocky, jagged ceiling blurred by the speed of the train. As your eyes adjust, the train emerges from the constricting tunnel to a series of large cavernous rooms, with ceilings hundreds of feet above you, the most striking being one illuminated by a large chandelier in the center. Each of these rooms is met with ooohs and ahhhs by the passengers of the train, identifying massive stalagmites and stalactites and the sheer scale of this karst system.

Suddenly, though, the train stops. Your guide tells you to please leave, and you embark on foot. Walking through this cave, now illuminated by lights pointed upwards, the massive size of the cave starts to become clear. At 24,340 meters long it seems impossible to explore fully, and with paved pathways marked obviously, the tour takes out any doubt as to whether or not you’re walking in the right direction. And, as with any tour, the group starts bunched up all walking next to the guide, but slowly stretches, and by the middle, you can find you and your companions alone in a gigantic cavern, staring at stalagmites over 5 meters tall. Which, in all honesty, was shocking, as one millimeter takes 10-20 years to form, a creation of slow, relentless drops of water. Near the end of the tour, the cave had one last surprise in store, an ability to see the famous baby dragons of Postojna, blind aquatic salamanders Proteus anguinus, known locally as Olm. These tiny white and slightly see-through salamanders live in the water depths of the cave, a marvel of the adaptability of nature in such a harsh, rocky environment. A trip to the gift shop and it was time for us to get back on the train towards the exit and our bed in Hotel Jama. I had experienced the cave world before as a child, in both Brazil and the United States, but I was flummoxed by the size and extensive network of caves carved out by the Pivka river over millions of years. To shoot it was challenging, with low-light conditions contrasted by the areas where floodlights illuminated a colorful, glimmering rock formation, but to get even the few shots I managed was this photographer’s dream come true.

Back at Hotel Jama, the sun setting one final time in Slovenia for my wife and I, I tried to internalize this quick, whirlwind of a trip. Since arriving back in London and writing this blog, I have continued that process. Slovenia, a tiny country, seemed to contain surprises in every little corner. Like a painter’s palette, dotted with all the colors in the spectrum, Slovenia was a microcosm of what seemed to be the best of all the countries it bordered, taking a little bit from here, something else from there to form a mixture of ethnic and European influences I had never experienced. In the north, as we found in Velika Planina, you encounter Alpine Europe, in the south east, Croatian influence, and in the south west, Italy is so close you can almost smell the pasta. Slovenia’s history was undoubtedly a key factor in the development of their modern-day culture and natural wonders. Centuries of rule by a variety of ethnic groups and tribes (Bavarians, Germans, Hungarians, Austrians, Venetians, and then finally as part of broader Yugoslavia) had suppressed Slovenians from expression and to develop their own industries at a large scale. The consequence was a hidden culture with gems to be found all around, habits and rituals of a people forced underground for generations, the pressure from above shaping into what it is today: Europe’s buried diamond, slowly being unearthed day by day. Furthermore, they were able to protect their natural habitats at a time when the rest of Europe was destroying theirs. Since the 18th century and industrial revolution, Slovenia has had little say over extraction of natural resources and being so small, they were rarely pursued for them as other countries might have been as subjects of a foreign ruler. Now in the age of climate change and natural conservation, Slovenia is miles ahead of many of its neighbors, presenting tourists and environmentalists with fresh Alpine air, stunning river valleys (like Soča), forests, caves, and more. This from a country smaller than the American state of Massachusetts.

For someone who knew nothing about the country other than Lake Bled, one can imagine the difficulty of trying to summarize the country or fit it into a box. There is truly nothing like it. My regrets lie only in a tight itinerary over far too few days.

What does that mean? I will be back. I must go back. I need to see Velika Planina in summer, when the herdsmen come with their cattle, turning a frosty mountain top into a thriving cultural center with lush green meadows. I need to see Soča Valley in fall, when the leaves change and the stunning blue river carves its way through the trees. And I need to have a glass of Slovenian wine whilst relaxing in one of their many, and famous, hot springs.

I’d say my wife probably finds the latter the top priority. Either way, I don’t mind, anything to convince her to go back with me. Another trip to Slovenia calls.